EMEL: The Tunisian Protest Singer Breaking Down Boundaries

Emel Mathlouthi is the Tunisian singer who became a hero of the revolution after a video of her singing in the streets at a martyrs’ funeral went viral during the Arab Spring in 2011.

Now living in New York, she is releasing her second album, a cross-border collaboration with cutting-edge electronic producers that retains traditional instrumentation and her dazzling voice at its core, while wearing its love of humanity and freedom on its sleeve.

This morning, she has driven to the Good Trouble studio from her home in Harlem, bumping her new record in the car, and laughs that it only distracted her from her GPS once – “The bass sounds so loud and good!”

We are only a few days out from the launch of Ensen, which translates as ‘human’, and Emel is excited. Putting on her coat and earrings for the shoot, while applying makeup in a cracked mirror, she explains how the new album is much more than the ‘protest music’ with which she has been tagged.

“When I first listened to music, even if I didn't understand the lyrics, it filled me with emotions on many levels,” she explains. “There could be the human, the political, but also we need hope in everything, in our daily life. And strength, and trust, and faith. I think that's what I want to give to people through my music."

When Emel first started making music, she was in what she describes as the Tunisian underground scene, partly because of her political lyrics, but also her openness to experimentation with electronics and Western musical styles. Government repression and censorship led to her relocating to France in 2008, where she was pleased to find an audience interested in what she was doing, “even though it was in a language they didn't necessarily understand.”

However, she found herself struggling to shake off the ‘world music’ tag. “It's great to be programmed and have the chance to share your music, of course. At the same time, I would like to be part of a festival where you won’t necessarily find the flag of my country in the description.”

Even while she was looking for a home for this album (and she reels off a few well-known labels), she was told to try ‘world music’ specialists. “I would say, ‘Why? Did you listen to the music? Is it just because I'm singing in Arabic?’ I'm sure if I had sung in English, it would have been different.”

“Being a human is not about violence and hatred. Art is human… a beautiful thing that only a human being can do.”

To Emel, a beautiful melody can touch anyone, whether in the United States or north Africa. “That's why I wanted to name the album Ensen,” she adds, “because all the songs merge towards the contrasting sides of a human being – darkness, light, fragility, strength, madness… the joy, the hope, the pain… for me, that's the only chance we have to be able to connect, because being a human is not about violence and hatred. Art is human… a beautiful thing that only a human being can do.”

Emel says she saw this when she performed at the Nobel Peace Prize Concert in 2015. It was an audience that had no idea who she was. "It was very scary for me," she says, "because it was a very serious audience. But I was extremely, nicely surprised at the attention, with people really focusing on the emotion coming out of the stage.”

“Jay Leno, who was the host of the concert, came to me and said, ‘There's so much pop crap going on – what you do is different.’ I was really touched! And in the press conference, he said, ‘I have never listened to anything in Arabic before… I have never imagined there could be such beauty, that I could connect emotionally to something I don't understand the language of.’"

For this album, Emel struggled to find producers who understood her vision, instead of just creating a “bunch of things all over the place, not serving one central message.” She began recording with her live band in France but they became confused by the process of recording loops, so she collaborated with a friend from Tunisia who took a very “punk approach” to traditional instrumentation. “That's when we created the first track ‘Ensen Dhaif’ by having this very heavy drums and bass in the middle, but mixed with flutes.”

She also worked with Johannes Berglund in Stockholm, who added keyboards and drums, then Valgeir Sigurðsson in Iceland, who worked in a contemporary classical feel. She returned home to have her baby daughter, she continues, then connected with French/Tunisian producer Amine Metani to help pull it together at home in New York while she couldn’t travel.

“He brought the gumbrî, which is this huge Tunisian bass. It's from north Africa, but the Tunisian one is very special because it has this huge cylinder and is kind of a percussive instrument, it has animal skin. But it has a very limited range, so it was a big challenge to retune it and record small portions on the computer. I was really happy he had that openness, not just to treat that instrument traditionally but to really stretch it for us to get what we wanted.”

“I think the place where you have to feel the most comfortable and supported is your own country, right? I struggle in Europe, in America, but I also have to struggle to perform in my own country.”

Two songs on the album are some of the first she ever wrote, from back in 2004/2005. She used to perform them in Tunisia, sometimes with a reggae vibe, she smiles, and is excited to hear them reach their full potential. As well as some release dates in New York and Europe, she is now also preparing her Tunisian comeback. Despite Emel’s success following her protest anthem ‘Kelmti Horra (My Word Is Free)’ reaching millions of hits on YouTube and becoming the de facto anthem of the Arab Spring, she has not performed in her own country for five years.

“I think the place where you have to feel the most comfortable and supported is your own country, right?,” she says. “I struggle in Europe, in America, but I also have to struggle to perform in my own country.”

“I'm lucky because I'm recognized in my country, but I'm not mainstream. So, I’m going to defy all the old-minded people and government ministers, and perform at a big festival! In Tunisia, I'm seen as weird but with a beautiful voice – they recognize the quality, but at the same time, my music is too Westernized and theatrical. But I have this fantastic young audience I know could fill a huge space.”

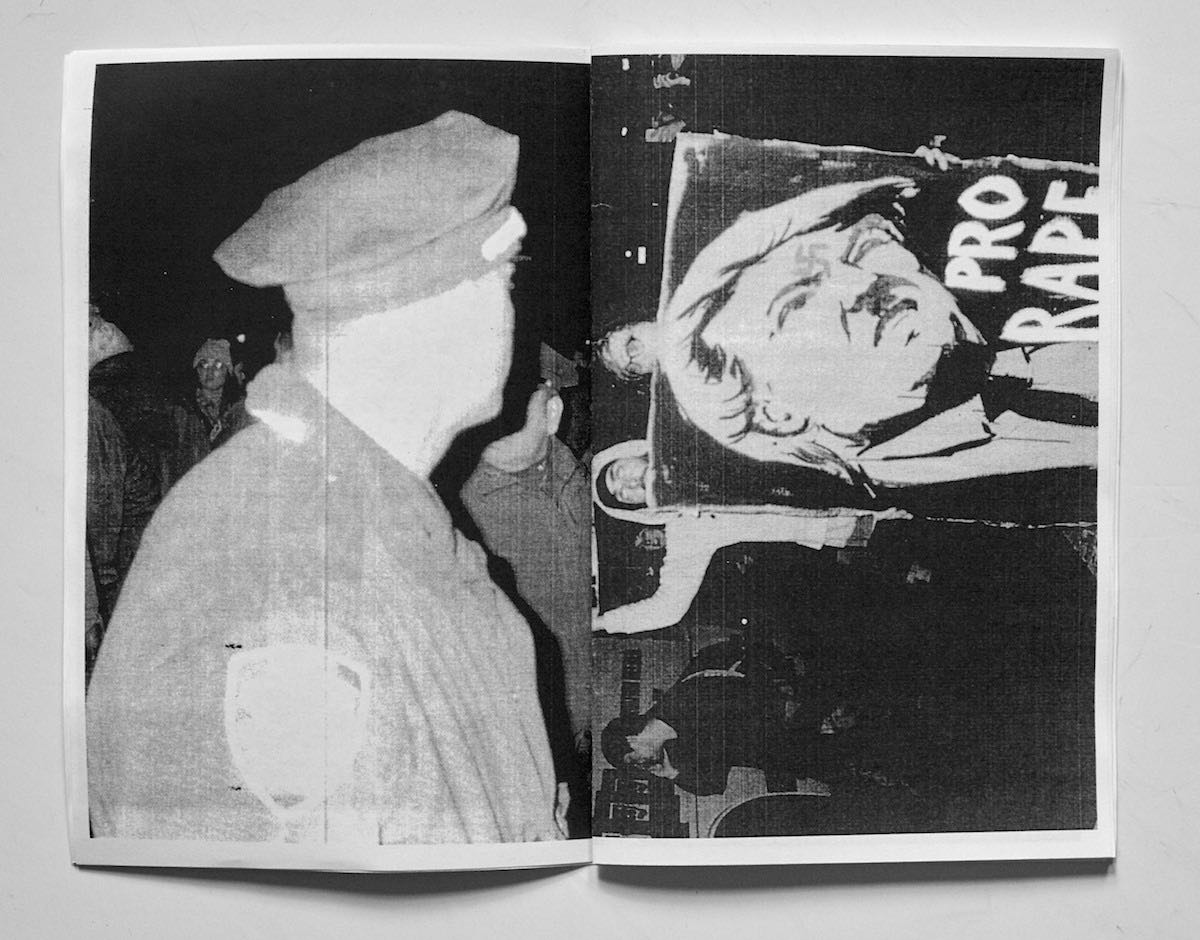

If it happens, it will of course be a vastly different experience to the time she spontaneously performed in the street during the 2010/11 revolution. “I don't do very spontaneous things like that. I'm very shy, like I don't even sing in the shower! But I was pushed, it was a tribute to the martyrs, so a very serious moment. And people were sitting on the ground with candles. Then, one of my friends who was an activist, lawyer and very, very strong woman, pushed me. She said, ‘We want you to sing here for us. Not in France. We want to hear it now.’”

Music at funerals in Tunisia was not permitted, and a few people at the back started getting aggressive. “That’s why there's a guy shouting, ‘Vas-y Emel!’ [Go on, Emel!]”

“I left right away. Because I didn't want to get in trouble, or run into angry people. It was definitely a positive impact but I didn't realize it was going to get viral. I traveled a few days later, then my youngest sister called me and she said ‘The video is everywhere!” I didn't even know that anybody was filming.”

Emel reflects on her early days making music as an angry young woman in Tunisia – her “boiling self” – and how she came to singing about revolution. “I wanted to make people believe it is possible,” she explains. “And I believed very strongly in it, you know? I miss those days. That flame.”

At university, she had a metal band, then she discovered classic protest singers like John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez; in 2002, they held a Dylan tribute concert as a large band with harmonica, piano and so on, which was her first time performing in a proper theatre. The university crowd was exciting, she explains, because you feel like you’re going to change the world, but it’s a bit of a bubble. “But when I started performing, I started getting interest from the older generation, the Marxists and intellectuals who thought the new generation was kind of lost.”

“So, that's when I started also developing my own songs. And it was true there wasn't any conscience in the country. Most people were just surviving, they didn't want to have anything to do with anybody who had different ideas. Censorship, auto-censorship and auto-auto-auto-censorship, you know what I mean?"

"And I started writing to try to push people to believe in themselves. You have to tell people, ‘Well, you do have an opinion, and your opinion matters. And your life matters.’”

“I started writing to tell people, ‘You have an opinion, and your opinion matters. And your life matters.’”

"People are so scared, you need to be brave. And you need to be empathetic to start this kind of work. For some people, like me, it came naturally. It was my only reason to live! Even today, when I sometimes get tired of the 'political' stamp, I still think I have a different way of seeing things. I care about things. I care about issues, and I try to express that, one way or another.”

Emel admires MIA as someone who has tirelessly worked to bring global politics into her art, and would love to connect with her. “She has this video where she's in the desert with all these guys,” talking about ‘Bad Girls’, shot by Romain Gavras in the Moroccan desert, with boy racers in kaffiyeh spinning and drifting their cars. “That's revolutionary, just to present those people as being cool, you know?”

Tunisia was not one of the countries named in the recent American ‘travel ban’, affecting immigration from Muslim-majority nations, but one wonders if she has any concerns about her upcoming travel. “I'm lucky enough now to have a green card. But it's not my nature to be worried. And for me, traveling has always been difficult, even though I consider myself lucky. Like right now, I have my show in London, but I'm super worried about the visa. And they’ve started doing biometric prints each time you enter the States. I don't know if it's the case for citizens, but I think it's like showing you are controlled. You're owned.”

As someone who grew up in an oppressive regime, she says it’s hard to tell whether there are actual similarities with the new administration in the US, or if people are exaggerating. “I think there's both,” she offers. “There's certainly reason to be worried, and it's cool to have people form a movement, but at the same time it creates paranoia. And paranoia creates more space to exploit. But in America, people can still be themselves better than anywhere else on the planet.”

“I’m going to play clubs in the Midwest, places that don’t necessarily welcome music like mine…Especially after all that’s been happening, to be singing in Arabic all over America!”

“I think it's important today to emphasize that art is more crucial than ever,” she adds. “In desperate places, when you get art and put it into a cultural centre, you help people explore their creativity, and it will change a lot of things. As soon as kids hear music, see an instrument and somebody playing, it develops a better mood. Better ideas.”

Emel is preparing to play more dates across America, and not just cultural festivals in big cities. “I’m going to play clubs in the Midwest, places that don't necessarily welcome music like mine," she says excitedly. "Especially after all that's been happening, to be singing in Arabic all over America!”

Does she consider herself brave – a woman, singing in Arabic, touring the stages of America’s red states at this time? “It's going to bring me right back to the centre of what I do –the music,” she answers. “I'm confident, but singing in Arabic definitely gives me this humility that brings me back to the beginning every time. Each time, you never know. It's good! I like to be challenged. When you're too confident, you stop being curious. It's funny because I'm pushing myself further, but I’m also kind of representing a whole culture.”

So, no pressure, then? “No pressure, right!”

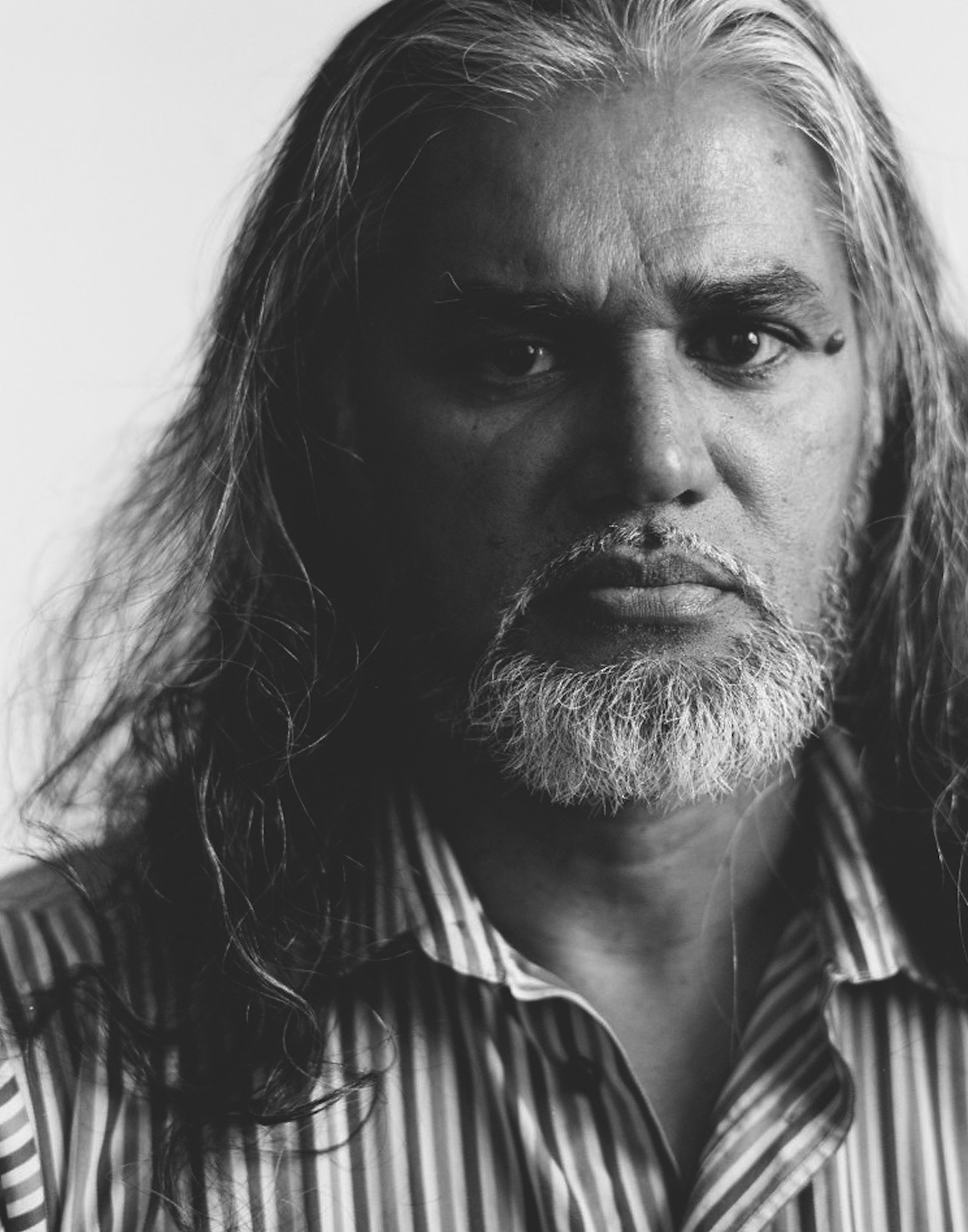

Emel photographed exclusively for Good Trouble by Alex Austin

Emel's ‘Ensen’ is out on Partisan Records from February 24

Live dates are here

Writer, editor and consultant based in London /New York