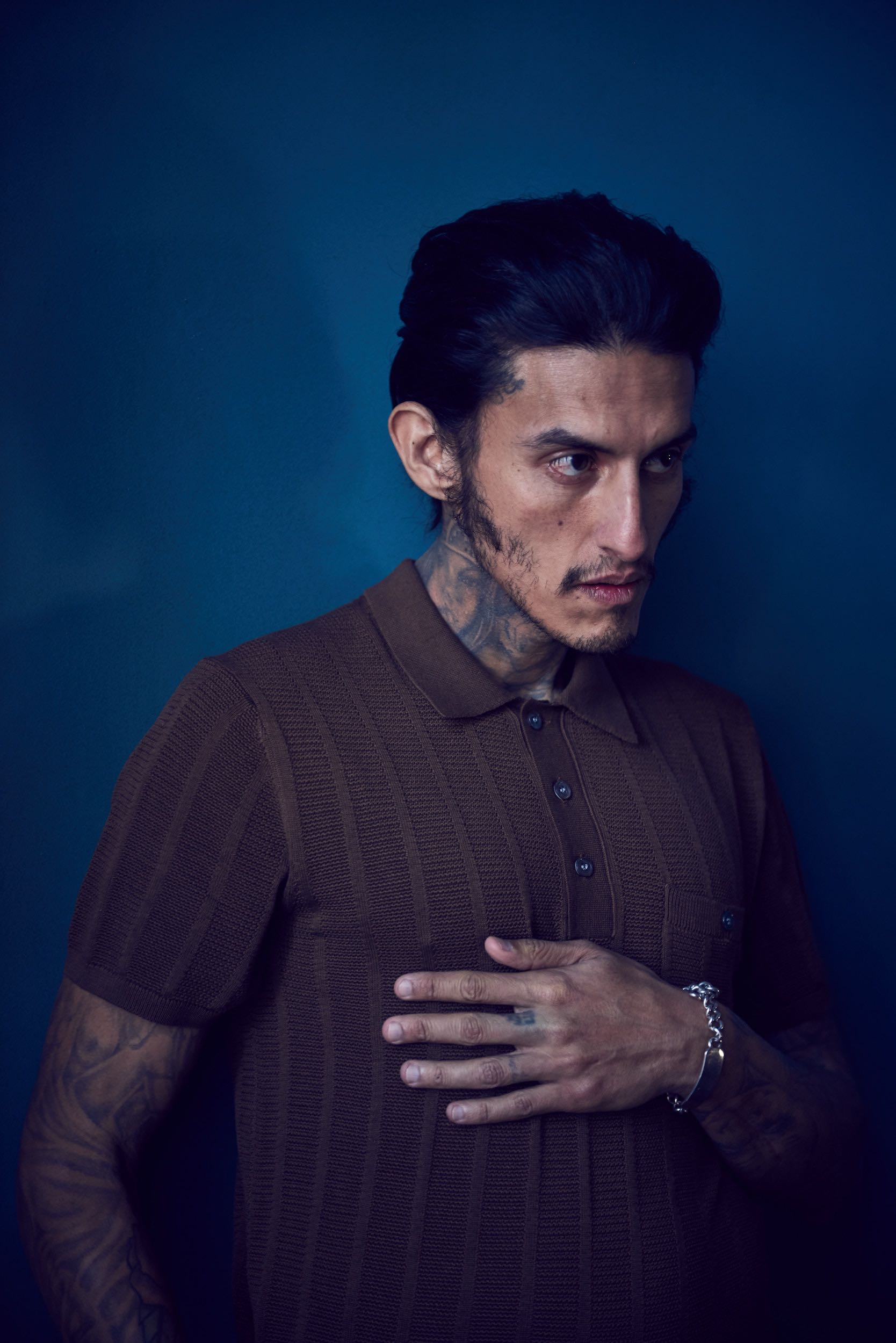

Richard Cabral: Actor, Poet, Gang Member, Activist

Richard Cabral is an LA-based actor and poet. He’s also a former gang member and convict. He tells GOOD TROUBLE his story. Photographs by James Mooney

Born in the mid-80s into a family of East LA gang members, Richard Cabral did his first time aged 13, going back to jail every year until he was 25. His longest stint, for an attempted murder, was his last. On getting out, he left the gang he had grown up in. With the help of local Christian organisation Homeboys Industries, he began mentoring those still caught up in gang life and prison, and embarked on a new career as an actor. He secured an Emmy nomination for his portrayal of Hector Tontz, a former gang member struggling to go straight, in the excellent ABC series American Crime, now in its third season.

“People see me how they see me, and that’s all they see,” Cabral’s character says at one point. And Cabral’s own story is one of identity and acceptance – of how the marks of a tough, violent past impact the present. But his story is also one of of how a hard history can be held close, and how loyalty – to himself, as well as his former fellow gang members – can allow a radical honesty to help others.

“I witnessed guns, and violence, and everything people growing up there witness,” he says, as we speak for an hour about prison reform, power and acting. “I finally came home at 25. And then it turned to what it is now.”

GOOD TROUBLE: Tell us about growing up in LA.

“I was born in 1983, when the crack epidemic hit. So, I guess you could say I was a product of that energy, that time, and that sickness. Gangs, murder, mass incarceration.”

Richard Cabral: I’m a second-generation Mexican-American, and I was raised by my mom in East Los Angeles. I didn’t grow up in the south or the west where there’s other culture, I grew up in a metropolis of just Mexicans. The inner cities of Los Angeles have been riddled with guns and drugs since the beginning – it was poor, and law enforcement just didn’t care. I was born in 1983, when the crack epidemic hit. So, I guess you could say I was a product of that energy, that time, and that sickness. Gangs, murder, mass incarceration.

LA historian Mike Davies said this explosion of gang violence from the 80s onwards is the result of deindustrialization. You have places where solidly middle-class and blue-collar jobs were disappearing, so people were just hanging around instead of working. And this coincides with the arrival of crack…

It was like these two forces that coincided at the same time. Boom. In the south side and in East LA, you have these cities which are all industrial. Right along the LA River, it’s all factories and warehouses. So, you those kids with the mind to work, but all you have are drugs. The knowledge now is methamphetamine, and has been for the last 15 years. And while it’s not as visible as the crack epidemic, it’s taken its toll on the communities. The craziness of the stories, mothers killing babies and shit, all that has to do with drugs. The drugs really fucked things up.

One thing I heard about solving gang violence was that only warriors can end the war. Would you agree?

Yeah, that’s a good one. For sure, for sure. To talk about the war, you have to know the war. To talk about death, you have to know death. So, I agree, in thousands of ways.

Being in a gang, you know there’s a very likely path, which is not the redemptive one you’ve encountered. Death or a lifetime in jail are very possible outcomes. What does that feel like?

There’s a normality to it. It’s the philosophy of a warrior, or a man in the army. It’s not abnormal to know you might die, because there’s a gang of other motherfuckers that might die with you. They all get it: we talk about death, and we talk about jail. The first time I went to jail as a kid, I looked around and thought ‘Oh! There’s hundreds of others like me.’ I break it down, like we are all trying to belong to something in the world. And if you belong to a community that doesn’t have shit, you’re going to belong to whatever it provides. I wish there was fucking Boy Scouts, or self-help groups where men mentored me: but there wasn’t. There wasn’t. To answer your question: everyone else is doing it. So, it’s not abnormal.

“You know the violence and craziness it carries, but you know they’re not bad people. They’re people.”

I remember being young and seeing my uncle go to prison. And subconsciously it became ingrained in me that it’s OK to go to prison. My uncle’s a gang member, and has been a gang member since before I was born. You look outside and see gang members. You know the violence and craziness it carries, but you know they’re not bad people. They’re people. You see that machismo is real, and you get to school, and see you that if you’re a punk, it’s going to be harder for you at school. So, you get tough.

What was the thing that turned it round for you?

“The truth was that I didn’t want to spend my life in prison.”

Fighting that life sentence being 20 years old, and God was talking to me in that real way, and you could try to stray from it, and believe you’re in some myth of this higher all-powerful gang-beaters, but when it comes down to it, you’re about to get life imprisonment. When you really own that moment, and you really realise you might never come home again. That shit is normal. There were hundreds like me. But when you go to sleep, you think ‘Fuck. I’m about to get life.’ Now you’re thinking about a higher thing – 'I might not see my mom again. My son is one year old.’ That was the opening that started me questioning. The truth was that I didn’t want to spend my life in prison.

I spent a whole year in the country jail. I had a whole year to think. And through my prayers or whatever, I got five years. And that was like [gasps]. But for that whole fucking year, you’re thinking you might never come home.

Prison reform underpins this conversation. What is the cumulative effect of these years getting handed down by the state on the communities affected?

“My best friend was 15 when he got life. Fifteen! California gives you life.”

Have you watched 13th on Netflix? It’s that. It strips these sons and these fathers from their community, so you fuck up the community by having all these kids grow up without their fathers and mothers. You destroy the community. My best friend was 15 when he got life. Fifteen! California gives you life.

You don’t seem to want to hide from the past you had. You’re very happy to talk about things you could be forgiven for not wanting to discuss.

I feel there’s a power in it. It’s a powerful thing to own something like that. Like, as a poet, you can take that pain, and turn it into beauty. With American Crime, I turned that true, fucked-up story into something beautiful. As an artist, as a writer, you try to draw from stuff. And my well is deep! On the other side, you could save people with this story. If I don’t embrace this, if I don’t stand behind it, and say this is what made me, and this is what’s going to make me now, I cannot be that inspiration. I cannot go into prisons and talk to people. If I was to tell people, ‘You all should be ashamed, you’re all fuck-ups, I’m a fuck-up,’ what is the brighter side of that? What is the result of that? This is the brighter side. Embracing it has been one of the most powerful things.

“You can save people with this story. If I don’t stand behind it, and say this is what made me, I cannot go into prisons and talk to people… be that inspiration…”

Do you worry about being typecast?

At the beginning, I didn’t care. I was like, ‘Fuck it. If they’re going to bring me in, cool.’ If they’re going to fly me around the world, pay me, what’s the problem? And if I’m playing gang members, then I know them – these people are three-dimensional, real people with lives, so it’s not boring to play. But now with the American Crime story, in the latest season, they’ve shot me into the unknown, covered my tattoos, and now I’m playing these regular people. So, that typecast has flown out the window.

What’s up next?

[That character is] Isaac Castillo. I’m a ranch hand. Richard is over here now. It’s never what’s on the skin, it’s what’s beneath the skin. That’s what Michael Fassbender, Meryl, all those Oscar actors – it’s your fucking soul you’re showing. That’s what I strive for as an artist. Not saying I’ll get there, but it’s what I strive for. My heart and soul are in this character, I’m really excited about it.

Was getting the Emmy nomination a validation?

Yeah, but a validation I wasn’t seeking. I’m happy now. I was in a cell eight years ago. Now I’m out and working and seeing my kids. So, if an award was going to make me, I’d have lost myself. But it was a surprise, because I just concentrate on the work, and this just meant people recognised the work.

What are your feelings about Trump, as a Mexican-American and as a prison-reform advocate?

“During Obama’s reign, he deported more than any other president in history, so we’ve always been in the shit in a way!”

Well, during Obama’s reign, he deported more than any other president in history, so we’ve always been in the shit in a way! And I definitely think we’re going to be up against some stuff. But when the threat becomes real evident, it makes people united. I really don’t let it affect me personally. I’m a spiritual person, and don’t like to give people my power. If I let someone piss me off, I’ve given them power. This. Too. Will. Pass. I’m just trying to use my energy to speak the truth. As a prison reformer, we’re in a good place. Lots of stuff needs to happen, but in California, laws are getting passed, and we just need to push on like that.

Richard Cabral can be seen next in upcoming Sons of Anarchy spinoff Mayans MC

With thanks to James Mooney

ACTIONS

Check out Homeboy Industries, the Christian organization that helps previously incarcerated gang members in LA, such as Cabral

The United States is home to the world's largest prison population. Support the NAACP campaigning for fairer criminal justice policies.

Founded in 1971, PEN's American prison writing project believes in the rehabilitative power of writing and you can find out more here

Cut50 is an ambitious attempt to drastically reduce the amount of people in America's jails – find out more here

Writer and editor based in Berlin.