Women. Now.

Three milestones in the history of the women’s rights movement frame the group exhibition Women. Now. at The Austrian Cultural Forum New York: 1918 when women in Austria were given the right to vote, 1920 when women in the United States were granted the same right, and 1968, the year the feminist avant-garde was formed. Women. Now. explores not only these landmark moments in which greater political equality was achieved but also the legacy of feminism and the women’s rights movement and its impact on contemporary culture and politics now.

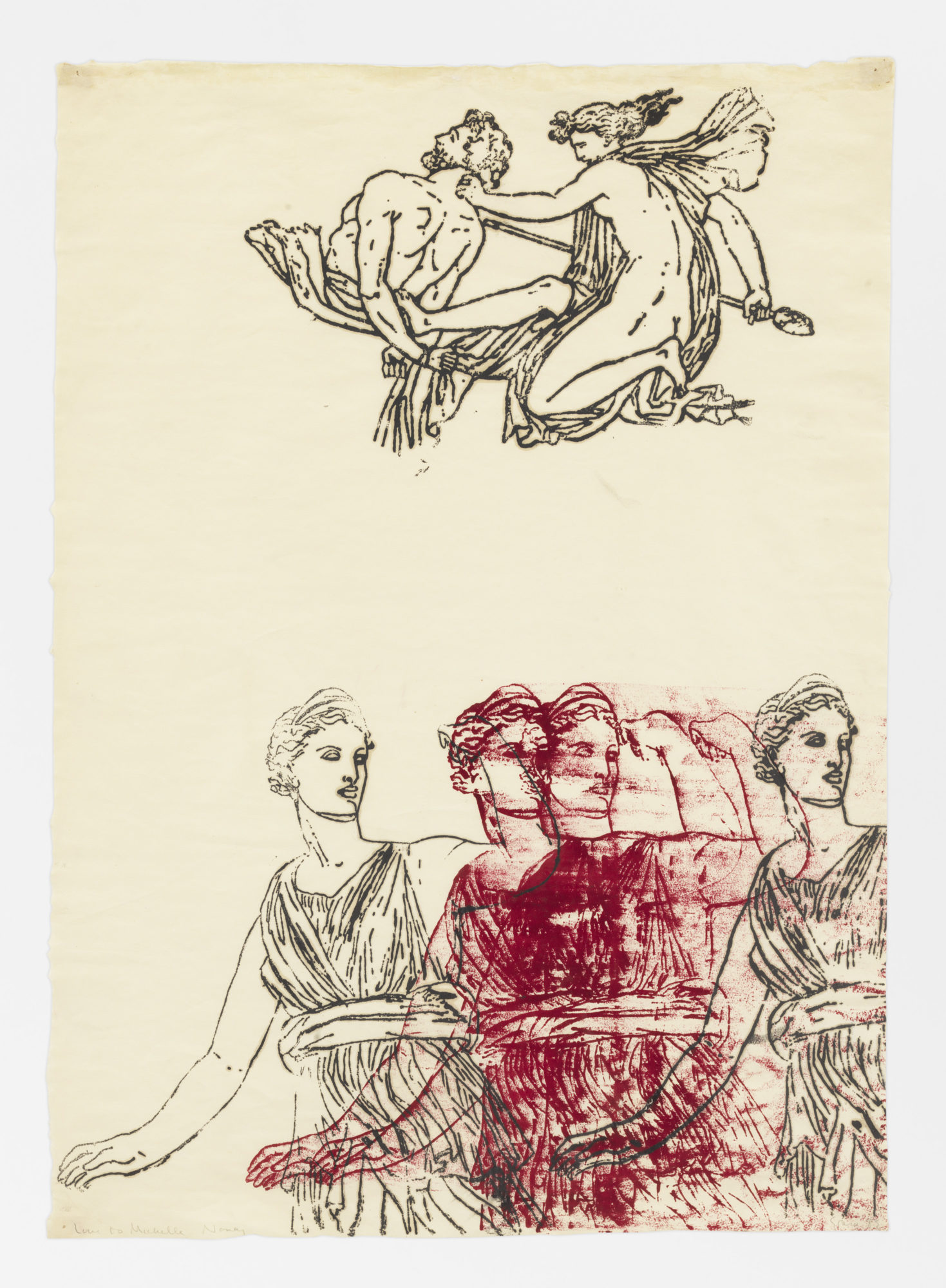

Beatrice Dreux’s Venus, 2015. Courtesy of the Artist and Smolka Contemporary.

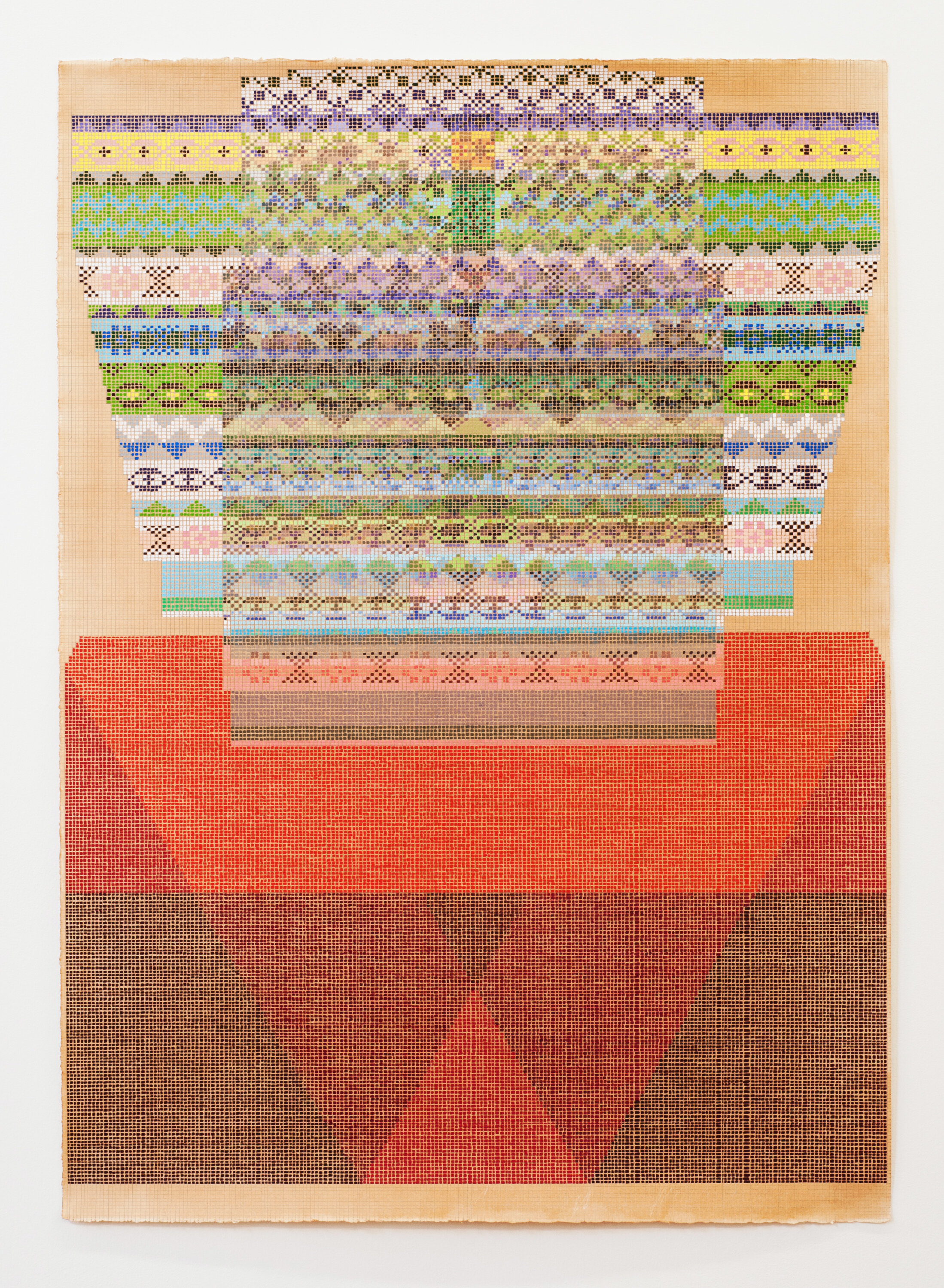

Female contemporary artists united across different generations address womanhood, arguing against social constructions regarding the role of women in society and rather promoting a more complex, inclusive, and multifaceted idea of “the feminine.” Artworks by Ellen Lesperance, Ines Doujak, and Uli Aigner give new purpose and power to materials traditionally associated with women like pottery and textile. Doujak, in particular, responds to worker exploitation and hierarchical abuse in the fashion industry. Margot Pilz in her short film sheds light on the stories of women, which have been habitually undervalued or ignored in historical narratives. Béatrice Dreux similarly empowers infamous mythical goddesses and priestesses, liberating these female figures from the male perspective from which their tales have been told. Both Sabine Jelinek and Eva Schlegel in their works consider freedom, the uncertainty of the term and women’s claim to it.

Martha Wilson’s Mona/Marcel/Marge, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York.

Sexuality and lust lie frequently at the forefront of debates considering women’s rights and freedoms, to choice in particular. What is the relationship of sexuality and lust to the body, to beauty, and to physical appearance? Artists Claudia Schumann, Frenzi Rigling, Titanilla Eisenhart, and Adriana Czernin all respond to this issue with resistance. Martha Wilson and Joan Semmel consider it in relationship to ageing. Sevda Chkoutova’s site-specific wall drawing and Heidi Harsieber’ two-piece photograph consider sexuality and lust as they relate to ideas and ideals of appearance while exploring the links between lust, violence, rapture, and passion.

These diverse female artists together question female identity: what is it to be feminine and what is it to be a woman? They redefine universalizing social constructions that lack malleability, individuality, and inclusivity while engaging creatively in current political discourses concerning gender discrimination and women’s rights and freedoms.

Here, curator Sabine Fellner and artist Sevda Chkoutova spoke with us individually about the exhibition and its significance now.

Margot Pilz’s HERSTORY – 36,000 Years of Goddesses and Idols, 2011/2012. Video with sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Why was it important to you to work with artists from different generations?

Sabine Fellner: “THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF OUR GENERATION ARE FRAGILE” pioneering feminist artist Annegret Soltau posted on Facebook, making it clear that the achievements of the feminist avant-garde formed in 1968, have to be reinforced on a daily basis. Looking back clarifies one’s own identity. Asking about the origin, about the attachment to the previous generation, allows one to locate oneself in the here and now. And one can, indeed, find frequent connections and references to the achievements of the older generation in young female artists’ work.

How did you decide what to focus on within the realm of women’s rights and freedoms and did this change with the time periods you’re considering?

SF: The artists deal with the prevailing view of women’s role in society. Their positions are characterized by a concern for fundamental existential questions, possibilities of self-development, one’s social position, women’s solidarity or competition, gender relationships, the question of guiding principles and beauty dictates, but also by a criticism of exploitative structures as well as gender and class hierarchies.

Betty Tomkins’s Women’s Words, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York.

The exhibition explores deeply existential questions that transcend cultural boundaries. Sevda Chkoutova's work examines female desire in the nexus of social attributions, norms, coercion, and self-experience. Feminist American artist Joan Semmel asks at the age of seventy what her place is in a society dominated by a cult of youth. Claudia Schumann, born in 1963, also takes up this aspect. Her photographic self-portrait in the form of a triptychon visualizes the confrontation with role expectations and beauty norms in a hauntingly painful way: she presses herself with an iron in order to make herself suitable and compliant.

As a female curator presenting a show consisting of all female artists, what are your thoughts on inclusivity in art? Do you think the art world is changing to allow for women artists and curators who’ve historically been underrepresented?

SF: By focusing entirely on female positions, Women. Now. aims to do its part to contribute to a society marked by gender equality. “The Great World Conspiracy" is the title of the recently opened exhibition in the NRW Forum in Düsseldorf. The fact that only two female positions are represented by 16 participating artists has led to a massive protest. It is shocking that in 2018, an exhibition hall financed by public funds will again host an exhibition with such a quota. The incident shows that there is still need for action. Women are still underrepresented.

Joan Semmel’s Centered, 2002. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates.

This is an exceptionally turbulent and precarious time for women’s rights and the feminist movement, especially or at least in America. What are your thoughts on presenting this exhibition right now?

SF: I hope that this exhibition gives impetus to critically examine the current situation of women and to recognize how much more needs to be done to achieve gender equality. I hope that Women. Now. visualizes how seriously and critically women artists deal with their present situation. Their positions are not only highly political like Ines Doujak's work but also visionary and global like Uli Aigner's One Million Project.

What is the role of art and creativity in activism and generating awareness around politics, social issues, human rights, etc.?

SF: Art is like a seismograph. It makes sociopolitical abuses visible long before they are discussed in public.

Sevda Chkoutova’s Untitled, 2018. India ink on wall over two floors. Courtesy of the artist.

What was the inspiration for your site-specific artwork for this exhibition? How did you respond to the exhibition’s subject?

Sevda Chkoutova: The wall which I worked on has two parts – the first one is situated on the ground floor and the second one on the upper floor. I’ve found the size and expanse of the whole wall over both floors very impressive, and I’ve seen an opportunity to contrast the content with the technique and to show they´re changing as the wall is getting higher.

The exhibition Women. Now. deals with women and their lives. As the name of the show suggests, so is my work closely linked to women’s life and reality. My wish was to work with the naked female body in order to represent two completely different parts of the female reality and its sense in only one work. The lower part of the wall drawing is concerned with domestic abuse and violence. In one part of the drawing, children and women have the same fate to live either with a violent father or husband. It is full of fear, violence, abuse, and pain. There is also interesting development in the work - the victims are turning into offenders. Over the course of time, not only the men but also the women who haven’t managed to escape from that reality are getting to be violent. The colors are deliberately held in grey and black in order to reinforce the intensity of the content.

The upper part of the wall drawing, however, is brighter and more clear. Only a few monster-like figures are trying to reach for the female naked body. Some of the victims have managed to escape from that painfully reality and made a fresh start. This is also a new start for their own body, life and sense. The protagonists are pleased, happy; they are proud of themselves, of their new bodies and their new sexuality. There are a lot of female bodies in the drawing, reflecting different ages and body types, but I always speak and think of only one body, because all of them have the same fate and fortunately also the opportunity to have and make their own choice.

Women. Now. is an exhibition about women and womanhood. The stories in my wall installation are surely for some women deeply familiar. It´s fair to say that the protagonists are fighting in order to stay alive. It´s a strong statement to put the female naked body at the center of an artwork in order to celebrate its liberty.

The ink work on the walls and the pencil sketch appear aesthetically quite different; they’re really interesting together. Can you tell me about the process of creating and putting them together?

SC: These two different aesthetics have a quite different significance to me. I come from that old school of drawing and love to represent something really photo-realistically with pencil on paper. The wall drawing, on the other hand, is a very intense way to work. I love it, too.

Sevda Chkoutova’s Untitled, 2018. Pencil and color pencil on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

They both are quite different, but they work together very well because of the theme of the whole work. The paperwork is a drawing, which is going to remain after the show, in contrast to the wall drawing, which is fleeting, as it will be painted over. I´ve chosen the paper, because it´s strong enough to carry the content of the lower wall. Simultaneously, in the drawing on paper, there is also the feeling of being free or not. This sense of freedom vs. captivity is also carried over to elements of the wall drawing. I wanted to create a work which carries the core themes of the wall installation but which will remain after the exhibition since my wall drawing is site-specific and not permanent.

The wall drawing is very intense and will be painted over after the show closes. Important here was the idea of a mortality and memory and how experiences and incidents are being memorized in a human body. The body´s memory is always mutable and depends on one’s own mood and body feeling.

Women. Now. works across time. Your work specifically responds to the contemporary discourse surrounding sexuality and lust and its relationship to the body and beauty. How do you think it’s changed over time? How do you conceive of this relationship in the present?

Betty Tomkins’s Women’s Words, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York.

SC: Sexuality and lust were male for a long time. There was no place in society for the woman and her sexuality. “To have lust” meant to be “un-behaved”. The female body wasn´t really free. When a woman had a child, her body meant to be no longer attractive. Sexuality was a sensitive topic. A lot of young women seek cosmetic surgery or become anorexic and bulimic. But what is beauty actually, and what´s the power in it? I think, there was or there is an ideal of beauty in our society (I´m speaking about industrial countries), which is not really human. Beauty is natural and doesn´t need a “girly body.” Beauty needs facial wrinkles because a wrinkle means a story. To feel beauty means to accept the own body. To accept their own body means for most women to get a sense of freedom. Nowadays, we are witnesses of a new feminist movement and we hope again.

Women. Now. is at The Austrian Cultural Forum New York through February 18, 2019.

Featured artists: Uli Aigner, Sevda Chkoutova, Adriana Czernin, Ines Doujak, Béatrice Dreux, Titanilla Eisenhart, Maria Hahnenkamp, Heidi Harsieber, Sabine Jelinek, Ellen Lesperance, Margot Pilz, Frenzi Rigling, Eva Schlegel, Claudia Schumann, Joan Semmel, Betty Tompkins and Martha Wilson.